By Bret Contreras

Every week or two, somebody tags me hoping I’ll chime in on a Facebook debate surrounding the hip thrust exercise. I wanted to write this response to save me time so that from now on I can just post this link (others can just post this link as well). Here’s how the arguments usually go:

1. It’s Good to Be Skeptical, but Don’t be a Bully

I start off my seminars informing the attendees to question everything, including everything I tell them. I inform them that I’m probably wrong about a few things I say in my presentations and that in a few years I’ll likely feel differently about some of the information. It’s good to be skeptical. But it’s not good to be a bully. I don’t give a damn how strong you are – being strong doesn’t make you right. I don’t give a damn how great your physique is – being huge or shredded doesn’t make you right either. If strength and hypertrophy were the end-all-be-all for credibility, then Mr. Olympia Phil Heath and strongest raw powerlifter Stan Efferding would make all the rules in sports science. While I enjoy learning about these lifter’s methods, they are not sports scientists and they aren’t the most intelligent biomechanists or sports scientists in the world (nor do they claim to be). Moreover, they don’t train clients regularly and track data.

2. A Training Study (or two or three) is Needed

I can sit here and speculate and rattle off theory, but at the end of the day a good training study is needed to show actual statistics. This will come in time.

3. Absence of Evidence is Not Evidence of Absence

However, just because a training study doesn’t exist, it doesn’t mean that a theory isn’t legit.

4. Evidence-Based Coaching Requires Consideration of Literature, Logic/Scientific Reasoning, and Anecdotes

When quality research isn’t available, we must rely on lesser forms of evidence, including logic and scientific reasoning, as well as anecdotal experience. Click HERE to learn more about the hierarchy of knowledge.

5. There’s Nothing Magical about Squats and Deadlifts

Squats and deads are my two favorite exercises. Squats work the hell out of the quads, they work the glutes in a stretched position, and they build good core stability, at least from an anti-flexion standpoint. Deadlifts work the hell out of the hammies, they work the glutes very well, especially in the flexed-hip position, they hammer the back musculature, and they also build incredible core stability in the same fashion as the squat. Both of these exercsies work tons of muscle, which raises the metabolic rate like crazy. Last, they lend themselves incredibly well to progressive overload – a critical component to success in strength, hypertrophy, power, and fat-loss.

However, like most good things, they are a double-edge sword. The hormone response that you think is so valuable (squats and deads jack up testosterone and growth hormone) is overrated. There is plenty of research on this – squats and deads don’t make the other muscles in the body grow larger like you think. They make the muscles that are highly activated grow larger, but muscles such as the pecs and triceps won’t grow from these movements.

Squats and deads don’t maximize glute activation, they don’t maximize hip extension torque, and they leave some room on the table in terms of glute development (more on this later). Moreover, squats and deads are better-suited for certain body types. Many lifters will never be good squatters. Some are forced to lean over considerably in the deadlift and also the squat due to their body structure, which places large amounts of loading on the spine. This incredible demand on the spine does indeed build core stability, but this comes at a price as it also increases the risks. Squats and deads do require skill; there are many exercises that are simpler and easier to master. Squats and deads have probably led to more injuries in the gym than any lifts in existence. If the lifter has a good coach or training partner, the risks can be severely reduced, however, not everyone has this luxury.

If you train a lot of people, you realize that they’re not all squatting and deadlifting the way they should be. When you encourage them to just load up on squats and deads, you could be inadvertently leading them toward injury. And in attempts to use heavier loads, many individuals compromise knee, hip, or spinal mechanics, which is why they’re dangerous. Many lifters fear injury so they never progress very far in squat and deadlift strength, and therefore they leave tons of room on the table for glute development if these are the only two lifts they perform.

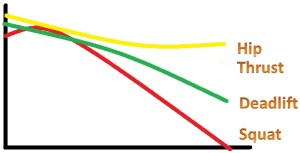

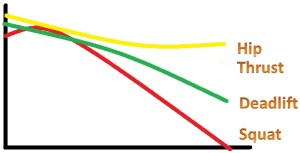

Here is my theoretical chart of hypertrophic adaptations following a year of proper resistance training:

As you can see, some lifts are better than others for different purposes, but all three in combination yield maximal results.

6. Logic, Common Sense, and Scientific Conjecture

Think about the bench press. Strength coaches worldwide love it. All lineman and shotputters perform it because it works the upper body pressing muscles incredibly well, which transfers to their performance. It does not replicate any functional movement patterns. If you want to replicate functional movement patterns, then perform a split stance cable chest press. You’ll look very functional, yet you won’t elicit the same torque loading and muscle activation in the shoulder musculature, nor will you produce as much force or power, nor will you see as much transfer to training. In the weight-room, we build strength, power, and muscle mass, and we coordinate all of the raw materials on the field.

The bench press provides a stable base with four points of support and takes advantage of gravity to work the shoulders from a horizontal vector.

The hip thrust is actually the lower body equivalent to the bench press. It provides three points of support and takes advantage of gravity to work the hips from a horizontal vector.

The lifter is not limited by core stability and spinal extension strength or by balance and coordination. There is no learning curve to the hip thrust – many people master it in their first training session, whereas squats and deadlifts can take years to truly master. The hip thrust is very conducive to progressive overload – perhaps more so than almost any other hip extension exercise as form is not much of a factor (it’s a simple lift). This is very important for maximal gains over time. Many lifters aren’t very coordinated and their body types (especially many women) aren’t well suited for squats and deads. This doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t do them; it just means that they shouldn’t be over-focused on progressive overload on these particular exercises. Conversely, every single body type is well-suited for hip thrusts (unless the lifter has a large gut and therefore has problems placing the bar on the hips).

For the first time, many lifters can use their hips to full capacity with the hip thrust. Essentially, you’re pushing straight down on the hips and telling your glutes to contract against resistance. It’s like doing a concentration curl for the glutes.

7. Muscle Activation

Due to several factors, the hip thrust greatly outperforms squats and deadlifts in glute activation. First and foremost, the glutes are activated to a much greater degree at end-range hip extension when the muscles are at short muscle lengths. I have nearly a dozen research papers and a ton of my own EMG experiments to substantiate this claim. HERE is one such paper.

Second, the extreme stability allows for greater activation (3 points of support as opposed to 2). Think bench press versus cable chest press; think deadlift versus single leg RDL on Bosu ball. In the case of the glutes, stability increases activation.

Third, the knees stay bent, which slackens the hamstrings. The higher up you rise in the hip thrust, the more the hamstrings shorten (hip extension and knee flexion both shorten the hammies). This is called “active insufficiency,” whereby the hammies can’t contribute their full force potential, and the glutes are forced to pick up the slack to create the requisite hip extension torque. In other words, the hip thrust equates to less hamstring force and more gluteus force.

Forth, when challenged to maintain anterior pelvic tilt, the glutes don’t fire as hard. This is the case with squats and deads. Don’t believe me? Arch your back as hard as possible and squeeze the glutes. Now get into a neutral spinal position and squeeze the glutes. Huge difference.

Since the hip thrust doesn’t require extreme anterior pelvic tilt torque like squats and deads, the glutes can fire harder. Furthermore, the glutes actually are challenged not only as hip extensors but also as posterior pelvic tilters during the hip thrust. The glutes must stabilize the pelvis so it doesn’t drift anteriorly (as an anti-anterior tilter), so even if the pelvis doesn’t posteriorly tilt, the torque (or moment) is there, sort of like the anti-extension torque on the spine in a plank.

The Hip Thruster is the best way to do the hip thrust – stable and versatile!

Fifth, the hip thrust activates the upper glutes to a much greater extent than squats, and even to a greater extent than deadlifts.

And sixth, EMG rises as a high rep set ensues as the nervous system attempts to compensate for diminished muscle force and contractile efficiency due to fatigue by recruiting more motor units. Many lifters can’t push their squats and deadlifts to ultimate muscular fatigue since their form breaks down too much. Often I have to stop my client’s sets far short of failure on squats and deads even though their glutes aren’t fully fatigued on account of rounding spines, caving knees, and excessive forward leans. However, with hip thrusts the set typically ends when the glutes are burning so badly that they can’t complete another rep. Therefore, the hip thrust leads to greater fatigue of the fibers and greater intensity of effort for the glutes, and this fatigue is critical for maximal hypertrophic gains.

For these reasons, the glutes fire 1.5-3 times harder in a hip thrust compared to a squat depending on whether examining the mean or peak activation levels. How can this increased activation, when coupled with progressive overload, not matter?

8. Torque Angle Curves

If muscle activation ain’t your thang, then perhaps you care about Physics, Biomechanics, Mathematics, and Engineering. In Hip Extension Torque, Chris and I teach you all about torque and how to calculate torque measurements.

When measuring the hip extension torque angle curves of squats, deadlifts, and hip thrusts, you’ll notice two things. First, that those with experience in all three lifts can achieve much higher hip extension torque levels with hip thrusting. This is due to the stability as well as the decreased demand on the spinal extensors. Many coaches believe that the spine is the limiting factor with squats and deadlifts, and I’d agree with them. Conversely, the hips are the limiting factor with the hip thrust. And second, that the hip extension torque does not drop off at the end-range of movement like it does during squats and deads.

Hip Extension Moment-Angle Curves During 500 lb Squat, Deadlift, and Hip Thrust

* Bear in mind that most lifters with experience with all 3 lifts can hip thrust and deadlift much more than they can squat – this graph assumes equal strength.

Squats and deads are not highly loaded at the top of the movements in terms of hip loading. The hips are essentially resting at lockout (there’s some tension on the hip extensors with the deadlift but nowhere close to what you see in the hip thrust). This has some practical implications. The key factors in hypertrophy are mechanical tension, metabolic stress, and muscle damage. Metabolic stress likely explains why bodybuilders are more muscular than powerlifters despite the fact that powerlifters place more absolute tension on the muscles. This greater constant tension on the glutes with the hip thrust is important for muscle hypertrophy via increased time under tension (TUT) and increased metabolic stress.

9. But it’s Not Functional…or is it?

I’d like to see data on the breakdown of goals with personal training clients and general gym-goers. I’d venture to guess that 90% of lifters have physique goals as their primary concern, with only 10% having functional/athletic goals as their primary concern. Personally, none of my clients come to me seeking improvements in function – they come to me seeking improvements in physique aesthetics. Therefore, I train them according to their goals. If their goal is powerlifting of sports performance, then I’d align their training to those goals, but this is rarely ever the case. Don’t place your goals onto your clients – that’s unethical.

But even more important is that you’re making assumptions about functionalism and transfer of training. Just like the bench press is functional, so is the hip thrust. So is the glute ham raise, various forms of planks, the back extension, the push-up, the reverse hyper, the pendulum quadruped hip extension, and inverted rows. They might be performed in a prone/supine position, but they transfer positively to performance due to their unique torque curves, very high torque loading and muscle force requirements, and/or stability. Much of what we do in the weight-room involves improving the hypertrophy, the neural drive, and the force and power potential in the muscle fibers. No matter how similar in movement pattern you think an exercise is to a functional activity, you must always coordinate the increased muscle output into the activity itself for maximal performance. This is why strength coaches always include various forms of jumps, sprints, and agility drills into their training – the weight-room cannot replace these actions. A quality strength training program for sport incorporates exercises from a variety of positions, including standing, supine, prone, and split-stance.

I venture to guess that over time we’ll discover that squats are better than hip thrusts for functional activities that are limited by knee strength and functional activities that resemble squatting (for example, jumping). I also venture to guess that over time we’ll discover that hip thrusts are better than squats for functional activities that are limited by hip strength and functional activities that resemble gait (for example, sprinting). Deadlifts would probably either fall in the middle on both categories, or they could outperform both.

End-range hip extension strength is of huge importance in sport, as is glute hypertrophy, as is horizontal force production, as is pelvic stability from an anteroposterior direction. For these reasons, you want to include the hip thrust into your training programs. Are you going to tell me with a serious face that an exercise that leads to greater glute activation, greater hip extension torque especially at end-range (the range where squats and deads are weakest and the range during ground contact in running), and an exercise that packs serious mass onto the glutes is not functional? If so, I have a hard time taking you seriously.

I believe that squats, deadlifts, and hip thrusts work synergistically with one another to maximize quad, hamstring, and glute size and strength, in addition to maximizing vertical and horizontal power production and squat/hinge/gait function. All three are required for maximum performance and full range hip extension, glute, and hamstring strength. In other words, they all provide value and an athlete should do them all.

10. My Own Experiences

My glutes are 5” bigger than my identical twin brother – he does squats and deads too but doesn’t focus on progressive overload like I do. I do squats, deadlifts, hip thrusts, and other hip strengthening movements, but I believe that the hip thrust explains some of this gap in glute girth.

Moreover, the hip thrust is the only exercise that I can perform where I feel a cramping and burning sensation in my glutes. This is evidence of muscle tension and metabolic stress. When I squat and deadlift, I don’t feel like my glutes are the limiting factor, however, when I hip thrust, the set ends when my glutes can no longer push the weight up. One time I had to end the set early during hip thrusts because I was worried that I was going to pull a glute muscle. I’ve never experienced this phenomenon with other exercises. Many times I can’t walk properly following hip thrusts since my glutes are so pumped up – it prevents me from achieving full hip extension ROM.

Furthermore, I still have the all-time record at Auckland University of Technology (AUT University) in hip extension strength as measured on an isokinetic dynamometer, and we’ve tested dozens of professional athletes (including pro rugby players from the best team in the world – some of whom can squat up to 800 pounds). I credit some of this to the hip thrust.

As a trainer, I believe that I can pack more glute size on my clients in three months of hip thrusting than I can in an entire year of squatting. After just 4 sessions or two weeks, many of my clients start noticing slight glute improvements. Before I started implementing the hip thrust, I could never in a million years showcase results this quickly. And I am incredibly skilled in developing strong squatters and deadlifters.

Even uncoordinated beginners can work their way up to 135 pound hip thrusts in a period of 2-8 weeks if they have proper coaching – the same can’t always be said of squats and deads as those patterns are sometimes limited by mobility or core stability deficits or motor patterning issues.

11. My Before/After Pictures

Take a look at the before/after pictures on the testimonials tab on this website. Nobody in the world that I know of has more impressive glute pics to my knowledge. Bear in mind that you probably haven’t trained as many people as I have, nor do you have as impressive of before/after pics. I’m here watching these transformations take place, so I know why it’s happening. When your before/after pics are better than mine, my ears will perk up and I’ll listen to you. These ladies’ glutes grew markedly which is what most women want for their physique. Many of them appeared to double their glute mass (increased their gluteus maximus cross-sectional area by 100%).

I can tell you that these ladies’ squat and deadlift strength probably went up 50-100% while training with me, but their hip thrust strength went up around 300%. I prioritized the hip thrust in every session and had them perform it first in the workout.

This transformation took place over a 6-month period. I’d estimate a 50% gain in glute muscle CSA. I didn’t push her squats – they only increased 20% in strength. However, we hip thrusted every session and she increased her hip thrust strength by 171%. She started off doing 105 x 12 reps and ended up doing 285 x 12 reps.

Each of these ladies could hip thrust over 225 pounds, and several of them can hip thrust 315 pounds for reps. Moreover, these ladies constantly remarked about how badly their glutes burned during the workouts, which is a huge indicator of metabolic stress. If you learn how to get very strong at the hip thrust with excellent form (or you learn how to get your clients very strong at the hip thrust), then I have no doubt that you’ll experience the same phenomenon.

12. Other’s Experiences

There are now thousands of lifters out there who have shared similar experiences. Not a day goes by where I don’t receive at least several emails from people who inform me that either 1) their glutes have grown markedly since implementing the hip thrust and barbell glute bridge, 2) they notice that they’re walking, running, or sprinting much faster after implementing the hip thrust and barbell glute bridge, and/or 3) their back pain has diminished after strengthening the glutes with hip thrusts and barbell glute bridges.

In our Get Glutes program, we have several hundred women remarking that they’re finally seeing good glute gains for the first time due to focusing on progressive overload, learning to activate the glutes, and prioritizing hip thrusts and bridges.

Even many highly reputable strength coaches, track & field coaches, and physical therapists have reported similar results, as will you.

13. Research Reports Averages

One drawback of research in general is that it reports averages. In general, I feel that the hip thrust is the best glute exercises in existence. However, there are occasional lifters who don’t seem to get as much tension in the glutes as others during the hip thrust. While I feel that this can be overcome in time with deliberate practice, it’s always good to employ a variety of glute exercises to ensure full activation of the array of fibers for all three gluteus maximus subdivisions.

Conclusion

Until you’ve trained yourself and others using the hip thrust just like thousands of trainers and lifters have done, you don’t really have a leg to stand on. Actually, until you’ve reached impressive strength levels training yourself and training others and documented the effects and listened to their feedback, you don’t really have a leg to stand on. It’s not just doing the hip thrust that matters – it’s getting freaky strong at the hip thrust that delivers the results.

The squat and deadlift are the kings of exercises and will never be replaced in the S&C kingdom. I do them and I have all of my clients do them. Nobody is suggesting that you quit squatting and deadlifting. Rather, the legion of hip thrusters is merely suggesting that you add them into your programming for synergy, maximum glute hypertrophy, end-range hip extension strength, proper lumbopelvic function, and maximum speed production.

Good goals for 200 pound athletic males are 405 pound hip thrusts for 5 reps in a year or two of solid training. Good goals for 130 pound athletic females are 225 pound hip thrusts for 10 reps in a year or two of solid training. Start folks out with bodyweight, make them squeeze the top for a split second on every rep, and gradually add load. In time they’ll be throwing up some large loads. But you can’t just wing-it. You have to adhere to a scientific approach to glute building, which is exactly what Kellie and I do in Strong Curves and what Kellie, Marriane, and I do in Get Glutes.

I realize that I need to produce some high-quality studies so we can learn more about the science of hip thrusting, but in the meantime, I’m going to keep doing my thing when training as the results are impossible to ignore. I hope you’ve found this article to be of value. In short, don’t knock it until you’ve tried it.

Every week or two, somebody tags me hoping I’ll chime in on a Facebook debate surrounding the hip thrust exercise. I wanted to write this response to save me time so that from now on I can just post this link (others can just post this link as well). Here’s how the arguments usually go:

- Attractive woman mentions on Facebook that she loves hip thrusts

- Psychic broseph with no experience with the hip thrust comments that she should just do squats and deadlifts and quit wasting her time with silly exercises

- Attractive woman replies, stating that she’s seen better results in glute development with hip thrusts in just a few months than she has in the previous year or two with squats and deadlifts

- Strong psychic broseph says that she’s just imagining things and that she doesn’t need to do them since squats and deadlifts reign superior for all things strength and hypertrophy related

1. It’s Good to Be Skeptical, but Don’t be a Bully

I start off my seminars informing the attendees to question everything, including everything I tell them. I inform them that I’m probably wrong about a few things I say in my presentations and that in a few years I’ll likely feel differently about some of the information. It’s good to be skeptical. But it’s not good to be a bully. I don’t give a damn how strong you are – being strong doesn’t make you right. I don’t give a damn how great your physique is – being huge or shredded doesn’t make you right either. If strength and hypertrophy were the end-all-be-all for credibility, then Mr. Olympia Phil Heath and strongest raw powerlifter Stan Efferding would make all the rules in sports science. While I enjoy learning about these lifter’s methods, they are not sports scientists and they aren’t the most intelligent biomechanists or sports scientists in the world (nor do they claim to be). Moreover, they don’t train clients regularly and track data.

2. A Training Study (or two or three) is Needed

I can sit here and speculate and rattle off theory, but at the end of the day a good training study is needed to show actual statistics. This will come in time.

3. Absence of Evidence is Not Evidence of Absence

However, just because a training study doesn’t exist, it doesn’t mean that a theory isn’t legit.

4. Evidence-Based Coaching Requires Consideration of Literature, Logic/Scientific Reasoning, and Anecdotes

When quality research isn’t available, we must rely on lesser forms of evidence, including logic and scientific reasoning, as well as anecdotal experience. Click HERE to learn more about the hierarchy of knowledge.

5. There’s Nothing Magical about Squats and Deadlifts

Squats and deads are my two favorite exercises. Squats work the hell out of the quads, they work the glutes in a stretched position, and they build good core stability, at least from an anti-flexion standpoint. Deadlifts work the hell out of the hammies, they work the glutes very well, especially in the flexed-hip position, they hammer the back musculature, and they also build incredible core stability in the same fashion as the squat. Both of these exercsies work tons of muscle, which raises the metabolic rate like crazy. Last, they lend themselves incredibly well to progressive overload – a critical component to success in strength, hypertrophy, power, and fat-loss.

However, like most good things, they are a double-edge sword. The hormone response that you think is so valuable (squats and deads jack up testosterone and growth hormone) is overrated. There is plenty of research on this – squats and deads don’t make the other muscles in the body grow larger like you think. They make the muscles that are highly activated grow larger, but muscles such as the pecs and triceps won’t grow from these movements.

Squats and deads don’t maximize glute activation, they don’t maximize hip extension torque, and they leave some room on the table in terms of glute development (more on this later). Moreover, squats and deads are better-suited for certain body types. Many lifters will never be good squatters. Some are forced to lean over considerably in the deadlift and also the squat due to their body structure, which places large amounts of loading on the spine. This incredible demand on the spine does indeed build core stability, but this comes at a price as it also increases the risks. Squats and deads do require skill; there are many exercises that are simpler and easier to master. Squats and deads have probably led to more injuries in the gym than any lifts in existence. If the lifter has a good coach or training partner, the risks can be severely reduced, however, not everyone has this luxury.

If you train a lot of people, you realize that they’re not all squatting and deadlifting the way they should be. When you encourage them to just load up on squats and deads, you could be inadvertently leading them toward injury. And in attempts to use heavier loads, many individuals compromise knee, hip, or spinal mechanics, which is why they’re dangerous. Many lifters fear injury so they never progress very far in squat and deadlift strength, and therefore they leave tons of room on the table for glute development if these are the only two lifts they perform.

Here is my theoretical chart of hypertrophic adaptations following a year of proper resistance training:

As you can see, some lifts are better than others for different purposes, but all three in combination yield maximal results.

6. Logic, Common Sense, and Scientific Conjecture

Think about the bench press. Strength coaches worldwide love it. All lineman and shotputters perform it because it works the upper body pressing muscles incredibly well, which transfers to their performance. It does not replicate any functional movement patterns. If you want to replicate functional movement patterns, then perform a split stance cable chest press. You’ll look very functional, yet you won’t elicit the same torque loading and muscle activation in the shoulder musculature, nor will you produce as much force or power, nor will you see as much transfer to training. In the weight-room, we build strength, power, and muscle mass, and we coordinate all of the raw materials on the field.

The bench press provides a stable base with four points of support and takes advantage of gravity to work the shoulders from a horizontal vector.

The hip thrust is actually the lower body equivalent to the bench press. It provides three points of support and takes advantage of gravity to work the hips from a horizontal vector.

The lifter is not limited by core stability and spinal extension strength or by balance and coordination. There is no learning curve to the hip thrust – many people master it in their first training session, whereas squats and deadlifts can take years to truly master. The hip thrust is very conducive to progressive overload – perhaps more so than almost any other hip extension exercise as form is not much of a factor (it’s a simple lift). This is very important for maximal gains over time. Many lifters aren’t very coordinated and their body types (especially many women) aren’t well suited for squats and deads. This doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t do them; it just means that they shouldn’t be over-focused on progressive overload on these particular exercises. Conversely, every single body type is well-suited for hip thrusts (unless the lifter has a large gut and therefore has problems placing the bar on the hips).

For the first time, many lifters can use their hips to full capacity with the hip thrust. Essentially, you’re pushing straight down on the hips and telling your glutes to contract against resistance. It’s like doing a concentration curl for the glutes.

7. Muscle Activation

Due to several factors, the hip thrust greatly outperforms squats and deadlifts in glute activation. First and foremost, the glutes are activated to a much greater degree at end-range hip extension when the muscles are at short muscle lengths. I have nearly a dozen research papers and a ton of my own EMG experiments to substantiate this claim. HERE is one such paper.

Second, the extreme stability allows for greater activation (3 points of support as opposed to 2). Think bench press versus cable chest press; think deadlift versus single leg RDL on Bosu ball. In the case of the glutes, stability increases activation.

Third, the knees stay bent, which slackens the hamstrings. The higher up you rise in the hip thrust, the more the hamstrings shorten (hip extension and knee flexion both shorten the hammies). This is called “active insufficiency,” whereby the hammies can’t contribute their full force potential, and the glutes are forced to pick up the slack to create the requisite hip extension torque. In other words, the hip thrust equates to less hamstring force and more gluteus force.

Forth, when challenged to maintain anterior pelvic tilt, the glutes don’t fire as hard. This is the case with squats and deads. Don’t believe me? Arch your back as hard as possible and squeeze the glutes. Now get into a neutral spinal position and squeeze the glutes. Huge difference.

Since the hip thrust doesn’t require extreme anterior pelvic tilt torque like squats and deads, the glutes can fire harder. Furthermore, the glutes actually are challenged not only as hip extensors but also as posterior pelvic tilters during the hip thrust. The glutes must stabilize the pelvis so it doesn’t drift anteriorly (as an anti-anterior tilter), so even if the pelvis doesn’t posteriorly tilt, the torque (or moment) is there, sort of like the anti-extension torque on the spine in a plank.

The Hip Thruster is the best way to do the hip thrust – stable and versatile!

Fifth, the hip thrust activates the upper glutes to a much greater extent than squats, and even to a greater extent than deadlifts.

And sixth, EMG rises as a high rep set ensues as the nervous system attempts to compensate for diminished muscle force and contractile efficiency due to fatigue by recruiting more motor units. Many lifters can’t push their squats and deadlifts to ultimate muscular fatigue since their form breaks down too much. Often I have to stop my client’s sets far short of failure on squats and deads even though their glutes aren’t fully fatigued on account of rounding spines, caving knees, and excessive forward leans. However, with hip thrusts the set typically ends when the glutes are burning so badly that they can’t complete another rep. Therefore, the hip thrust leads to greater fatigue of the fibers and greater intensity of effort for the glutes, and this fatigue is critical for maximal hypertrophic gains.

For these reasons, the glutes fire 1.5-3 times harder in a hip thrust compared to a squat depending on whether examining the mean or peak activation levels. How can this increased activation, when coupled with progressive overload, not matter?

8. Torque Angle Curves

If muscle activation ain’t your thang, then perhaps you care about Physics, Biomechanics, Mathematics, and Engineering. In Hip Extension Torque, Chris and I teach you all about torque and how to calculate torque measurements.

When measuring the hip extension torque angle curves of squats, deadlifts, and hip thrusts, you’ll notice two things. First, that those with experience in all three lifts can achieve much higher hip extension torque levels with hip thrusting. This is due to the stability as well as the decreased demand on the spinal extensors. Many coaches believe that the spine is the limiting factor with squats and deadlifts, and I’d agree with them. Conversely, the hips are the limiting factor with the hip thrust. And second, that the hip extension torque does not drop off at the end-range of movement like it does during squats and deads.

Hip Extension Moment-Angle Curves During 500 lb Squat, Deadlift, and Hip Thrust

* Bear in mind that most lifters with experience with all 3 lifts can hip thrust and deadlift much more than they can squat – this graph assumes equal strength.

Squats and deads are not highly loaded at the top of the movements in terms of hip loading. The hips are essentially resting at lockout (there’s some tension on the hip extensors with the deadlift but nowhere close to what you see in the hip thrust). This has some practical implications. The key factors in hypertrophy are mechanical tension, metabolic stress, and muscle damage. Metabolic stress likely explains why bodybuilders are more muscular than powerlifters despite the fact that powerlifters place more absolute tension on the muscles. This greater constant tension on the glutes with the hip thrust is important for muscle hypertrophy via increased time under tension (TUT) and increased metabolic stress.

9. But it’s Not Functional…or is it?

I’d like to see data on the breakdown of goals with personal training clients and general gym-goers. I’d venture to guess that 90% of lifters have physique goals as their primary concern, with only 10% having functional/athletic goals as their primary concern. Personally, none of my clients come to me seeking improvements in function – they come to me seeking improvements in physique aesthetics. Therefore, I train them according to their goals. If their goal is powerlifting of sports performance, then I’d align their training to those goals, but this is rarely ever the case. Don’t place your goals onto your clients – that’s unethical.

But even more important is that you’re making assumptions about functionalism and transfer of training. Just like the bench press is functional, so is the hip thrust. So is the glute ham raise, various forms of planks, the back extension, the push-up, the reverse hyper, the pendulum quadruped hip extension, and inverted rows. They might be performed in a prone/supine position, but they transfer positively to performance due to their unique torque curves, very high torque loading and muscle force requirements, and/or stability. Much of what we do in the weight-room involves improving the hypertrophy, the neural drive, and the force and power potential in the muscle fibers. No matter how similar in movement pattern you think an exercise is to a functional activity, you must always coordinate the increased muscle output into the activity itself for maximal performance. This is why strength coaches always include various forms of jumps, sprints, and agility drills into their training – the weight-room cannot replace these actions. A quality strength training program for sport incorporates exercises from a variety of positions, including standing, supine, prone, and split-stance.

I venture to guess that over time we’ll discover that squats are better than hip thrusts for functional activities that are limited by knee strength and functional activities that resemble squatting (for example, jumping). I also venture to guess that over time we’ll discover that hip thrusts are better than squats for functional activities that are limited by hip strength and functional activities that resemble gait (for example, sprinting). Deadlifts would probably either fall in the middle on both categories, or they could outperform both.

End-range hip extension strength is of huge importance in sport, as is glute hypertrophy, as is horizontal force production, as is pelvic stability from an anteroposterior direction. For these reasons, you want to include the hip thrust into your training programs. Are you going to tell me with a serious face that an exercise that leads to greater glute activation, greater hip extension torque especially at end-range (the range where squats and deads are weakest and the range during ground contact in running), and an exercise that packs serious mass onto the glutes is not functional? If so, I have a hard time taking you seriously.

I believe that squats, deadlifts, and hip thrusts work synergistically with one another to maximize quad, hamstring, and glute size and strength, in addition to maximizing vertical and horizontal power production and squat/hinge/gait function. All three are required for maximum performance and full range hip extension, glute, and hamstring strength. In other words, they all provide value and an athlete should do them all.

10. My Own Experiences

My glutes are 5” bigger than my identical twin brother – he does squats and deads too but doesn’t focus on progressive overload like I do. I do squats, deadlifts, hip thrusts, and other hip strengthening movements, but I believe that the hip thrust explains some of this gap in glute girth.

Moreover, the hip thrust is the only exercise that I can perform where I feel a cramping and burning sensation in my glutes. This is evidence of muscle tension and metabolic stress. When I squat and deadlift, I don’t feel like my glutes are the limiting factor, however, when I hip thrust, the set ends when my glutes can no longer push the weight up. One time I had to end the set early during hip thrusts because I was worried that I was going to pull a glute muscle. I’ve never experienced this phenomenon with other exercises. Many times I can’t walk properly following hip thrusts since my glutes are so pumped up – it prevents me from achieving full hip extension ROM.

Furthermore, I still have the all-time record at Auckland University of Technology (AUT University) in hip extension strength as measured on an isokinetic dynamometer, and we’ve tested dozens of professional athletes (including pro rugby players from the best team in the world – some of whom can squat up to 800 pounds). I credit some of this to the hip thrust.

As a trainer, I believe that I can pack more glute size on my clients in three months of hip thrusting than I can in an entire year of squatting. After just 4 sessions or two weeks, many of my clients start noticing slight glute improvements. Before I started implementing the hip thrust, I could never in a million years showcase results this quickly. And I am incredibly skilled in developing strong squatters and deadlifters.

Even uncoordinated beginners can work their way up to 135 pound hip thrusts in a period of 2-8 weeks if they have proper coaching – the same can’t always be said of squats and deads as those patterns are sometimes limited by mobility or core stability deficits or motor patterning issues.

11. My Before/After Pictures

Take a look at the before/after pictures on the testimonials tab on this website. Nobody in the world that I know of has more impressive glute pics to my knowledge. Bear in mind that you probably haven’t trained as many people as I have, nor do you have as impressive of before/after pics. I’m here watching these transformations take place, so I know why it’s happening. When your before/after pics are better than mine, my ears will perk up and I’ll listen to you. These ladies’ glutes grew markedly which is what most women want for their physique. Many of them appeared to double their glute mass (increased their gluteus maximus cross-sectional area by 100%).

I can tell you that these ladies’ squat and deadlift strength probably went up 50-100% while training with me, but their hip thrust strength went up around 300%. I prioritized the hip thrust in every session and had them perform it first in the workout.

This transformation took place over a 6-month period. I’d estimate a 50% gain in glute muscle CSA. I didn’t push her squats – they only increased 20% in strength. However, we hip thrusted every session and she increased her hip thrust strength by 171%. She started off doing 105 x 12 reps and ended up doing 285 x 12 reps.

Each of these ladies could hip thrust over 225 pounds, and several of them can hip thrust 315 pounds for reps. Moreover, these ladies constantly remarked about how badly their glutes burned during the workouts, which is a huge indicator of metabolic stress. If you learn how to get very strong at the hip thrust with excellent form (or you learn how to get your clients very strong at the hip thrust), then I have no doubt that you’ll experience the same phenomenon.

12. Other’s Experiences

There are now thousands of lifters out there who have shared similar experiences. Not a day goes by where I don’t receive at least several emails from people who inform me that either 1) their glutes have grown markedly since implementing the hip thrust and barbell glute bridge, 2) they notice that they’re walking, running, or sprinting much faster after implementing the hip thrust and barbell glute bridge, and/or 3) their back pain has diminished after strengthening the glutes with hip thrusts and barbell glute bridges.

In our Get Glutes program, we have several hundred women remarking that they’re finally seeing good glute gains for the first time due to focusing on progressive overload, learning to activate the glutes, and prioritizing hip thrusts and bridges.

Even many highly reputable strength coaches, track & field coaches, and physical therapists have reported similar results, as will you.

13. Research Reports Averages

One drawback of research in general is that it reports averages. In general, I feel that the hip thrust is the best glute exercises in existence. However, there are occasional lifters who don’t seem to get as much tension in the glutes as others during the hip thrust. While I feel that this can be overcome in time with deliberate practice, it’s always good to employ a variety of glute exercises to ensure full activation of the array of fibers for all three gluteus maximus subdivisions.

Conclusion

Until you’ve trained yourself and others using the hip thrust just like thousands of trainers and lifters have done, you don’t really have a leg to stand on. Actually, until you’ve reached impressive strength levels training yourself and training others and documented the effects and listened to their feedback, you don’t really have a leg to stand on. It’s not just doing the hip thrust that matters – it’s getting freaky strong at the hip thrust that delivers the results.

The squat and deadlift are the kings of exercises and will never be replaced in the S&C kingdom. I do them and I have all of my clients do them. Nobody is suggesting that you quit squatting and deadlifting. Rather, the legion of hip thrusters is merely suggesting that you add them into your programming for synergy, maximum glute hypertrophy, end-range hip extension strength, proper lumbopelvic function, and maximum speed production.

Good goals for 200 pound athletic males are 405 pound hip thrusts for 5 reps in a year or two of solid training. Good goals for 130 pound athletic females are 225 pound hip thrusts for 10 reps in a year or two of solid training. Start folks out with bodyweight, make them squeeze the top for a split second on every rep, and gradually add load. In time they’ll be throwing up some large loads. But you can’t just wing-it. You have to adhere to a scientific approach to glute building, which is exactly what Kellie and I do in Strong Curves and what Kellie, Marriane, and I do in Get Glutes.

I realize that I need to produce some high-quality studies so we can learn more about the science of hip thrusting, but in the meantime, I’m going to keep doing my thing when training as the results are impossible to ignore. I hope you’ve found this article to be of value. In short, don’t knock it until you’ve tried it.